SLUMBERLAND by paul beatty

a sly and outrageous book that i don’t know why isn’t getting more attention or wasn’t on any of the mainstream best of 08 lists. it may be provincial to say but i’ll read a hundred beatty’s before i read a book about friggin cricket.

a strange curse to be the smartest comedian in the room. my two pfennigs: paul beatty is the funniest american writer alive. a riff master, there‘s so much comic bravado packed into this one i had to keep putting it down to walk around the room, big grin on my face. comedians are a dangerous breed, sacrificing a lot for the punch line but needing the vinegar of truth to make it sting.

on race — SLUMBERLAND’s sub- supra- and ur- text — beatty’s not 100% right, but who is. and beatty’s usually nudging us to surprising recognitions. on the other hand, when he’s less honest or more cheap, we get: just gags or cheap shock and awe tactics.

structurally and language-wise, the book, which thankfully shows beatty recovered from the sophomore slump of TUFF, is whipsmart and quick-footed but not groundbreaking. it starts out irregular — a black american DJ in 1989 berlin — and turns quickly comic book-y irreal. or maybe: para-paranormal. the DJ is in berlin searching for a quasi-legendary jazz musician who was last heard on the soundtrack of a bestiality porn flick, specifically one where a man fucks a chicken (the man in the blue vid turns out to be a prognosticating stasi agent). the jazz musician — dubbed the schwa because his sound, “like the inderterminate vowel is unstressed, upside-down, and backward” — eventually reveals himself at the eponymous slumberland bar to perform a percussive tour de force using only a beat up copy of a faulkner paperback.

it weakens just a bit in the middle when the berlin wall falls and the narrative stalls discussing african east german experience with an oddly overly-academic sociology angle. characters are introduced to make points but not so we really need them. but that’s okay. DJ darky — our lead protag — has enough character to spare. (also, it’s impressive but a little tiring to read convincingly about all the various musical ecstasies, which happens alot) …but before too long the book re-finds its pace and hilariously works itself up to its plot crescendo of an ending.

a cliché and prolly a gratuitous aside: i think your contemporary comedian is one of the most tragic of beasts. absolutely self-willed to be impervious, there’s no possibility of intimacy. perhaps this is the point of the book — inescapable loneliness — and maybe i’m wrong, but the thing that seems to prevent SLUMBERLAND from sounding the real depths it seems capable of is its glibness.

but then. maybe glibness is the wrong word. the book seems to be fighting itself sometimes to exhaustion — jacob and the angel type combat — trying to become. and i felt very sympathetic in its struggle to be conflicting things at once. and maybe its glibness is in fact a method.

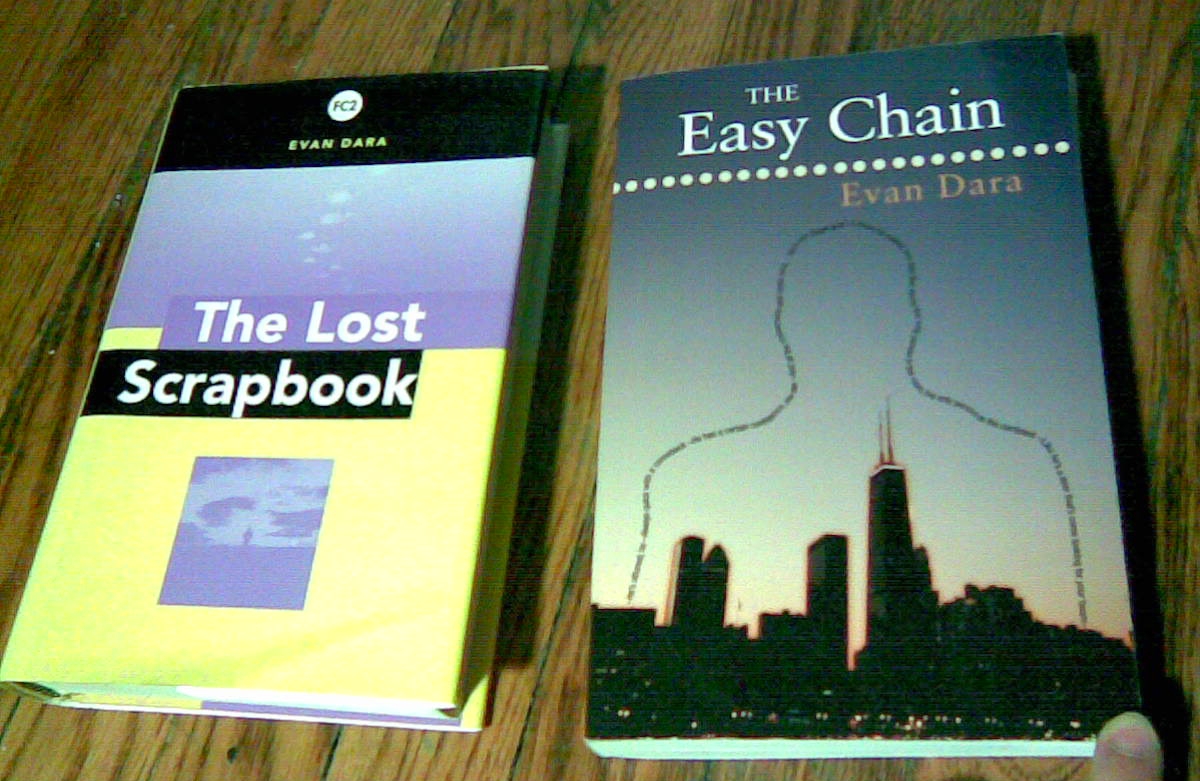

woah, just stumbled onto this. evan dara wrote a great book called

woah, just stumbled onto this. evan dara wrote a great book called  the female gaze. lydia sits at a bar and describes what she sees and imagines, most often: herself, other women. (how’s that for a plot!) a book of portraits, maybe a self-portrait, or maybe a book about portraiture–the ambiguity intentional and often successful as a statement about our success in ever describing completely an identity.

the female gaze. lydia sits at a bar and describes what she sees and imagines, most often: herself, other women. (how’s that for a plot!) a book of portraits, maybe a self-portrait, or maybe a book about portraiture–the ambiguity intentional and often successful as a statement about our success in ever describing completely an identity.

beckett and bernhard may be the basis of “Bee,” the writer whose suicide is the vacuum at the center of this novel. as such it makes sense that under the layer of gossipy bedswapping tales by intelligentsia and almost crudely titillating descriptions of common breakdowns and various life botchings is the novel’s real content–our natural state of depravity which makes such crudeness and vacuity our continued mode of being.

beckett and bernhard may be the basis of “Bee,” the writer whose suicide is the vacuum at the center of this novel. as such it makes sense that under the layer of gossipy bedswapping tales by intelligentsia and almost crudely titillating descriptions of common breakdowns and various life botchings is the novel’s real content–our natural state of depravity which makes such crudeness and vacuity our continued mode of being. a fascinating but subtly disappointing book, ann quin’s THREE is a formally radical novel. arguably more daring in form than her contemporary b. s. johnson–with whom she’s often lumped partly because they committed suicide in the same year–she’s here also more cagey and unfortunately more predictable.

a fascinating but subtly disappointing book, ann quin’s THREE is a formally radical novel. arguably more daring in form than her contemporary b. s. johnson–with whom she’s often lumped partly because they committed suicide in the same year–she’s here also more cagey and unfortunately more predictable.